What is anaesthesia?

Anaesthesia stops you feeling pain and unpleasant sensations. It can be given in various ways and does not always need to make you unconscious.

-

There are different types of anaesthesia, depending on the way they are given:

- Local anaesthesia involves injections that numb a small part of your body. You stay conscious but free from pain.

- Neuraxial or Regional anaesthesia, e.g. a spinal , epidural or nerve blocks involves injections that numb a larger or deeper part of the body. You stay conscious or receive some sedation, but are free from pain. For some surgeries you may be aware of pressure sensations.

- General anaesthesia gives a state of controlled unconsciousness. It is essential for some operations and procedures. You are unconscious and feel nothing.

- Sedation gives a ‘sleep like’ state and is often used with a local or regional anaesthetic. Sedation may be light or deep and you may remember everything, something or nothing after sedation.

Anaesthetists

-

Anaesthetists are doctors with specialist training who:

- Discuss with you the type or types of anesthetic that are suitable for your operation. If there are choices available, they’ll help you choose.

- Discuss the risks of anaesthesia with you

- Agree a plan with you for your anesthetic and pain control afterwards

- Give your anaesthetics and are responsible for your well being and safety throughout your surgery and in the recovery room.

Pre-Assessment clinic

-

If you’re having a planned operation you might be invited to pre-operative assessment clinic a few weeks or days before your surgery.

-

-

Please bring with you:

- Current prescription or bring your medicine in full packaging

- Any information you’ve about tests and treatments given other hospitals

- Information about any problems you or your family may had with anesthetics

-

-

Anaesthetists at the Pre- Anaesthetic Clinic will:

- Ask you in detail about your activity and any physical and mental health problems

- Ask you about allergies and reactions

- Make an accurate list of the medicine you take, including long term pain killers

- Ask you if you smoke, drink alcohol or take recreational drugs

- Weigh and measure you

- Take your blood pressure and check your heart rate and oxygen levels

- Listen to your heart and chest if required

- Arrange any blood tests as needed

- Perform an ECG ( heart tracing )

- Take a skin and/or nose swab to check for any infection

- Advise you on what medication you should take on the day of your surgery and what pain relief you should have ready at home for your recovery.

- Give your information about blood transfusions if they think you might need one

Before coming to hospital:

- If you smoke, giving up several weeks before the operation will reduce the risk of breathing problems during anesthetic and after your surgery.

- If you have obesity, reducing you weight will reduce many of the extra risks you face during your anesthetic and after your surgery.

- If you have loose teeth or crowns, a visit to your dentist before the operation may reduce the risks of damage to your teeth during the anesthetic.

- If you have a long standing medical problem that you feel is not well controlled ( eg: Diabetes, Asthma or bronchitis, Throid problems, chronic pain or heart problems ), check with your GP surgery if there is anything you can do to improve it

- It is also important that you consider any mental health concern such as anxiety and depression, as these too can make a difference to your surgery and recovery.

- If you return home the same day having had a general anesthetic or sedation, you will need to organise a responsible adult to take you home and stay with you for up to 24 hours.

On the day of your admission:

- If you’re diabetic, please check with your anesthetist when to stop eating and drinking and how you should take your medication on the day of your operation.

- If you’re a smoker, you should not smoke on the day of operation, as it reduces the amount oxygen in your blood.

- If you’re on medications, you should follow the specific instructions from the pre-operative assessment clinic about how to take them on day of the operation.

- If you’re taking any “blood-thinning” drugs such as warfarin, clopidogrel or rivaroxaban, you will need to discuss with the pre-operative assessment team when to stop taking them.

- Please remove nail varnish or gel before coming to the hospital. This ensures the clip on your finger to measure oxygen levels works well during your anesthetic.

Getting ready for your operation

Your nurse will give you a hospital gown to wear and discuss what underwear you’ll wear. You’ll usually wear elastic stockings to reduce the risk of blood clots in your legs. Your nurse will attach identity bands to your wrist or ankle and in some hospitals an additional band if you’ve any allergies.

Premedicationis sometimes given before some anaesthetics. Pre-meds prepare your body for surgery- they may start off the pain relief, reduce acid in the stomach or help you relax.

You should remove jewellery and/or any decorative piercings. If you cannot remove it, the nurses will cover it with tape to prevent damage to it or to your skin.

When you’re called for your operation

Routine checkswill be done as you arrive in the operating department, before the anesthetic starts. You’ll be asked your name, your date of birth, the operation you’re having, whether on the left or right side ( if applicable ), when you last ate or drank and if you have any allergies. These checks are routine in all hospitals.

Starting the anesthetics

Your anesthetic may start in the anesthetic room or in the operating theatre. Your anesthesist will be working with a trained assistant. The anesthesist or the assistant will attach leads to machines to measure your heart rate, blood pressure and oxygen levels and any other equipment as required.

A cannulaa small plastic tube inserted in your vein with a needle, is used to start most anesthetics in adults, including a local anesthetics. All drugs can then be given into your veins using the cannula.

-

Local and regional anesthetics

- Your anesthesist will ask you to keep still while injections are given. You may notice a warm tingling feeling as the anesthetic begins to take effect.

- Your operation will only go ahead when you and your anesthesist are sure that the area is numb.

- You’ll remain alert and aware of your surroundings, unless you’re having sedation. A screen will stop you seeing the operation unless you want to.

- For regional anesthetics, a member of the anesthetic team is always near to you and you can speak to them whenever you want to.

If you’re having local or regional anesthetics:

The recovery room

After the operation, you will usually be taken to the recovery room. Recovery staff will make sure you’re as comfortable as possible and give any extra medication you may need. When they’re satisfied that you’ve recovered safely from your anesthetics and there is a bed available, you’ll be taken back to the ward.

Pain relief after surgery

The type and amount of pain relief you’ll be offered will depend on the operation you’re having and your pain levels after the operation. Some people need more pain relief than others.

Generally some degree of pain or discomfort should be expected during your recovery. Stronger pain killers can be very good at relieving pain, but may have side effects, like nausea, constipation, and addiction in the long term.

-

Here are some ways of giving pain relief:

- Pills, tablets or liquids to swallow-these are used for all types of pain. They typically take at least half an hour to work. You need to be able to eat, drink and not feel sick for these drugs to work.

- Injections- These may be intravenous ( through your cannula into a vein for a quicker effect ) or intramuscular ( into your leg or buttock muscle using a needle, taking about 20 minutes to work)

- Suppositories- these waxy pellets are put in your rectum (back passage). The pellet dissolves and the drug passes into the body. They’re useful if you cannot swallow or if you might vomit.

- Local anaesthetics and regional blocks- these types of anaesthesia can be very useful for relieving pain after surgery.

Risks and anaesthesia

Modern anaesthetics are very safe. There are some common side effects from the anaesthetic drugs or the equipment used, which are usually not serious or long lasting. Risks will vary between individuals and will depend on the procedure and anaesthetic technique used.

Your anaesthetist will discuss with you the risks that they believe to be more significant for you. There are other less common risks that your anaesthetist will not normally discuss routinely unless they believe you’re at higher risk.

-

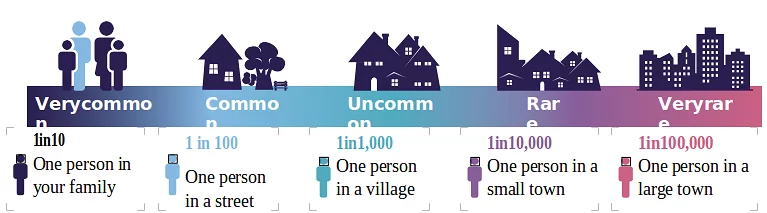

Very common- more than 1 in 10 ( equivalent to 1 person in your family )

- Sickness

- Shivering

- Thirst

- Sore throat

- Bruising

- Temporary memory loss ( mainly in over 60s )

-

Common- more than 1 in 10 ( equivalent to 1 person in your family )

- Pain at the injection site

- Minor lip or tongue injury

-

Uncommon-Between 1 in 100 and 1 in 1000 ( Equivalent to 1 person in a village)

- Minor nerve injury

-

Rare-Between 1 in 1000 and 1 in 10000 ( Equivalent to1 person in a small town)

- 1 in 1000 peripheral nerve damage that is permanent.

- 1 in 2800 corneal abrasions ( scratch on eye )

- 1 in 4500 damage to teeth requiring treatment,

- 1 in 10000 Anaphylaxis ( severe allergic reaction to a drug)

-

Very rare- Between 1 in 10000 to 1 in 100000 or more ( Equivalent to 1 person in a large town)

- 1 in 20000 awareness during anaesthetics

- 1 in 100000 lost of vision

- 1 in 100000 death as a direct result of anaesthesia

General Anaesthesia

The first section of this leaflet explains what the airway is, why anaesthetists need to manage it and how they do this during your anaesthetic.

It also explains how anaesthetists assess your airway ahead of surgery for any potential problems and the common risks associated with airway management.

The second section explains more detail about what happens if the management of your airway requires more planning and preparation.

Standard airway management

The airway

The airway, or breathing passage, is the path air takes to reach your lungs. When you breathe in, the air enters through your nose and mouth and flows through your throat, larynx (voicebox) and trachea (windpipe) to reach your lungs. Your body takes the oxygen it needs from this air.

During anaesthesia, anaesthetic gases can be mixed with this air to help keep you asleep during the operation.

Why anaesthetists need to ‘manage’ the airway during anaesthesia

As well as giving the anaesthetic, anaesthetists are responsible for your wellbeing for the duration of the surgery. This includes ensuring that your lungs continue to receive oxygen while you are anaesthetised.

This is particularly important during a general anaesthetic or deep sedation, as the muscles around your tongue and throat relax and could block the airway. The anaesthetist will plan how best to prevent this from happening. This is called ‘managing’ the airway.

How anaesthetists ‘manage’ the airway

The most important gas you will be given is oxygen. Before the anaesthetic begins you may be asked to breathe oxygen from a plastic face mask or from soft plastic tubes in your nostrils. This gives your lungs extra oxygen before the anaesthetic starts.

Anaesthetists have different methods and equipment to help them manage your airway. These will vary depending on their choices, on you as a patient and on the type of operation you are going to have.

There are different types of tubes that could be placed either in the mouth, within the throat or in the trachea, to open the airway and enable oxygen and anesthetic gases to be delivered easily to the lungs. These devices are normally put in after you are asleep (or are deeply sedated) so you will have no knowledge or memory of their use or insertion. The placement of a tube into your trachea (windpipe) is known as ‘tracheal intubation’.

How anaesthetists assess your airway

Before you have an anaesthetic, your anaesthetist or a member of their team will want to ask you a variety of questions, so that the best plan can be made for your anaesthetic and the management of your airway. If previously you were told about any difficulties managing your airway and breathing, you should inform the anaesthetist. They will also look at records from your previous anaesthetics if they are available.

They will ask about relevant medical conditions, for example arthritis in your neck, obstructive sleep apnoea or acid reflux.

Your anaesthetist may perform a few tests to help predict which type of airway management is needed for your situation. For example:

- They will usually check you can open your mouth widely and look at the back of your throat

- They may ask you to move your bottom jaw forward or to bite your top lip

- If you have a growth or swelling in your airway or neck, they will look at ultrasound or CT scans

- They may also look through your nose with a small flexible camera. This is painless.

Risks and common events associated with managing airways

People vary in how they interpret words and numbers. This scale is provided to help.

Sore throat

Putting airway equipment into your throat can cause a sore throat after your operation. This is very common.

Dental damage and injuries to your lips or tongue

There is a risk of damage to your teeth, lips and tongue when the breathing tube is being placed or removed. This is more likely if you have fragile teeth, crowns or an airway that is difficult to manage. Minor bruising or small splits to the lips or tongue are common and happen in about 1 in 20 anaesthetics. Minor injuries usually heal quickly. Damage to teeth requiring treatment is uncommon and happens 1 in every 4,500 anaesthetics to healthy teeth.

Failed intubation

Although it is uncommon, the anaesthetist may find it difficult or impossible to place an endotracheal tube into your windpipe. This is called a failed intubation. If this happens the anaesthetist may need to wake you up and postpone your surgery. Failed intubation happens around 1 in 2,000 anaesthetics for planned surgery. It is more common in emergency surgery and higher still in pregnant patients having emergency anaesthesia, where it occurs in approximately 1 in 300 anaesthetics.

Serious complications

On rare occasions, there may be serious complications due to problems with patients’ airways.

One cause may be stomach contents going into the lungs. This is called ‘aspiration.’ To minimise this risk, patients are routinely advised not to eat for six hours before planned surgery and some are also given tablets to reduce the amount of acid in the stomach.

Although very rare, other serious complications may lead to death, brain damage and unexpected admission to intensive care.

Accidental awareness during general anaesthesia

Awareness occurs when you become conscious during the time you were expecting to be asleep. It is rare, occurring in approximately 1 in 20,000 anaesthetics.

Awareness is more common at the time of starting the anaesthetic and waking up. If your airway is difficult to manage there is a greater chance of awareness during this time.

What you can do to reduce risks

Teeth

Make sure your teeth and any dental work such as crowns or bridges are secure and healthy before an anaesthetic (visit a dentist if needed). This will reduce the risk of them being damaged and reduces the risk of a tooth becoming loose and falling into the airway.

Starvation and pre-medication to prevent aspiration

Follow any instructions you are given on when you should stop eating and drinking before your anaesthetic. This is usually six hours for food and two hours for water. You should also take any medication to reduce the risk of aspiration as prescribed by the anaesthetist.

Obstructive sleep apnoea

If you have obstructive sleep apnoea, this will place you at higher risk of airway difficulties and you will need to be closely monitored following your anaesthetic. You may need to stay overnight in hospital, even for minor procedures. If you have a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine you should bring it with you to the hospital. You will often use it during your recovery from your anaesthetic

Beards and facial hair

Thick beards make it more difficult to look after your airway as face masks may not fit as snugly on your face. Thinning out your beard or shaving it off will help. Your anaesthetist may ask you to shave it completely.

Patient choice

If there are expected difficulties in managing your airway, anaesthetists should offer a full explanation and discuss any options for managing your airway with you.

Management of ‘difficult’ airways

This section explains what happens if the management of your airway is thought to need more planning and preparation.

What can make an airway ‘difficult’

There are several factors that alone or together might suggest that the management of your airway may be more ‘difficult.’ This means that the anaesthetist is likely to use more specialised equipment or techniques before and during anaesthesia.

-

Some factors may be to do with the shape and condition of your mouth, jaw and neck, for example:

- difficulty in opening your mouth

- loose teeth

- small lower jaw

- large beards

- injury or swelling of your airway (mouth, jaw, throat, neck).

-

Others may be to do with medical conditions or previous medical treatments:

- obesity

- obstructive sleep apnoea

- severe reflux or vomiting

- pregnancy

- rheumatoid arthritis

- tumour or growth in the airway (cancer and non-cancer)

- radiotherapy to your head or neck

- a record of complications from a previous anaesthetic.

How anaesthetists look after a ‘difficult’ airway

Your anaesthetist will consider the best method to manage your airway, based on their assessment and the results of any tests. If your anaesthetist thinks the management of your airway may require additional interventions, they will discuss with you the options available to keep you safe during the operation.

Awake or sedated tracheal intubation

Uncommonly, if there are likely to be significant difficulties using the usual approach to intubation, the anaesthetist may suggest an ‘awake’ (or sedated) intubation. In this case the tube is placed into your trachea while you are awake or sedated. This way, if the intubation is difficult or fails, they can just stop, and you continue to breathe on your own. If sedation is used, you may have little memory of the procedure.

Awake intubation is carried out in the anaesthetic room or operating theatre. Your anaesthetist will connect you to various machines to monitor your blood pressure, heart function and oxygen levels. They will, the same as for any anaesthetic, place a cannula (a thin plastic tube through which drugs can be injected) in your hand or arm. You will also be given oxygen through a mask or a soft plastic tube inside your nostrils.

Your anaesthetist will carefully spray local anaesthetic inside your nose, mouth and throat several times to make them numb. The local anaesthetic may make you cough and may affect your ability to swallow. This is normal and your anaesthetist will look after you to make sure you are safe.

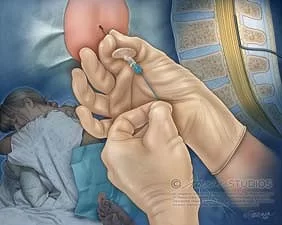

Once the area is numb, the anaesthetist will pass a small flexible tube attached to a camera through your mouth or nose. This guides the breathing tube into your trachea. Once the breathing tube is safely in place, your anaesthetist will start the general anaesthetic and you will become unconscious.

Spinal anaesthesia

For many operations it is usual for patients to have a general anaesthetic. However, for operations in the lower part of the body, sometimes it is often possible for you to have a spinal anaesthetic instead. This is when an anaesthetic is injected into your lower back (between the bones of your spine). This makes the lower part of the body numb so you do not feel the pain of the operation and can stay awake.

Typically, a spinal lasts one to two hours. Other drugs may be injected at the same time to help with pain relief for many hours after the anaesthetic has worn off.

During your spinal anaesthetic you may be fully awake or sedated with drugs that make you relaxed, but not unconscious.

Your anesthetist can help you decide which of these would be best for you.

-

A spinal anaesthetic can often be used on its own or with a general anaesthetic for:

- Orthopaedic surgery on joints or bones of the leg

- Groin hernia repair, varicose veins, haemorrhoid surgery (piles)

- Vascular surgery: operations on the blood vessels in the leg

- Gynaecology: prolapse repairs, hysteroscopy and some kinds of hysterectomy

- Urology: prostate surgery, bladder operations, genital surgery.

How is the spinal performed?

- You may have your spinal in the anaesthetic room or in the operating theatre. You will meet the anaesthetic assistant who is part of the team that will look after you.

- Your anaesthetist will first use a needle to insert a thin plastic tube (a ‘cannula’) into a vein in your hand or arm. This allows your anaesthetist to give you fluids and any drugs you may need.

- You will be helped into the correct position for the spinal. You will either sit on the side of the bed with your feet on a low stool or you will lie on your side, curled up with your knees tucked up towards your chest.

- The anaesthetic team will explain what is happening, so that you are aware of what is taking place.

A local anaesthetic is injected first to numb the skin and so make the spinal injection more comfortable. This will sting for a few seconds. The anaesthetist will give the spinal injection and you will need to keep still for this to be done. A nurse or healthcare assistant will usually support and reassure you during the injection

What will I feel (Spinal anesthesia)?

A spinal injection is often no more painful than having a blood test or having a cannula inserted. It may take a few minutes to perform, but may take longer if you have had any problems with your back or have obesity.

- During the injection you may feel pins and needles or a sharp pain in one of your legs – if you do, try to remain still, and tell your anaesthetist.

- When the injection is finished, you will usually be asked to lie flat if you have been sitting up. The spinal usually begins to have an effect within a few minutes.

- To start with, your skin will feel warm, then numb to the touch and then gradually you will feel your legs becoming heavier and more difficult to move.

- When the injection is working fully, you will be unable to lift your legs up or feel any pain in the lower part of the body.

Testing if the spinal has worked

-

Your anaesthetist will use a range of simple tests to see if the anaesthetic is working properly, which may include:

- spraying a cold liquid and ask if you can feel it as cold

- brushing a swab or a probe on your skin and asking what you can feel

- asking you to lift your legs.

It is important to concentrate during these tests so that you and your anaesthetist can be reassured that the anaesthetic is working. The anaesthetist will only allow the surgery to begin when they are satisfied that the anaesthetic is working.

Why have a spinal?

-

The advantages of spinal alone compared with having a general anaesthetic may be:

- a lower risk of a chest infection after surgery

- less effect on the lungs and the breathing

- good pain relief immediately after surgery

- less need for strong pain-relieving drugs that can have side effects

- less sickness and vomiting

- earlier return to drinking and eating after surgery.

During the operation (spinal anaesthetic alone)

- In the operating theatre, a full team of staff will look after you. If you are awake, they will introduce themselves and try to put you at ease.

- You will be positioned for the operation. You should tell your anaesthetist if there is something that will make you more comfortable, such as an extra pillow or an armrest.

- You may be given oxygen to breathe, through a lightweight, clear plastic mask, to improve oxygen levels in your blood.

- You will be aware of the ‘hustle and bustle’ of the operating theatre, but you will be able to relax, with your anaesthetist looking after you.

- You can talk with the anaesthetist and anaesthetic assistant during the operation.

If you have sedation during the operation, you will be relaxed and may be sleepy. You may snooze through the operation, or you may be awake during some or all of it. You may remember some, none or all of your time in theatre.

- your anaesthetist cannot perform the spinal

- the spinal does not work well enough around the area of the surgery

- the surgery is more complicated or takes longer than expected.

After the operation (spinal anaesthetic alone)

- It takes up to four hours for sensation (feeling) to fully return. You should tell the ward staff about any concerns or worries you may have.

- As sensation returns, you will usually feel some tingling. You may also become aware of some pain from the operation and you can ask for any pain relief you need.

- You may be unsteady on your feet when the spinal first wears off and may be a little lightheaded if your blood pressure is low. Please ask for help from the staff looking after you when you first get out of bed.

- You can usually eat and drink much sooner after a spinal anaesthetic than after a general anaesthetic.

Side effects and complications of spinal anaesthesia

As with all anaesthetic techniques, there is a possibility of unwanted side effects or complications with a spinal anaesthetic.

-

Very common events and common side effects

- Low blood pressure – as the spinal takes effect, it can lower your blood pressure. This can make you feel faint or sick. This will be controlled by your anaesthetist with the fluids given through your drip and by giving you drugs to raise your blood pressure.

- Itching – this can commonly occur if morphine-like drugs have been used in the spinal anaesthetic. If you have severe itching, a drug can be given to help.

- Difficulty passing urine (urinary retention) or loss of bladder control (incontinence) –you may find it difficult to empty your bladder normally while the spinal is working or, more rarely, you may have loss of bladder control. Your bladder function will return to normal after the spinal wears off. You may need to have a catheter placed in your bladder temporarily, while the spinal wears off and for a short time afterwards. Your bowel function is not affected by the spinal.

- Pain during the injection – if you feel pain in places other than where the needle is – you should immediately tell your anaesthetist. This might be in your legs or bottom, and might be due to the needle touching a nerve. The needle will be repositioned.

- Post-dural puncture headache – there are many causes of headache after an operation, including being dehydrated, not eating and anxiety. Most headaches can be treated with simple pain relief. Uncommonly, after a spinal it is possible to develop a more severe, persistent headache called a post-dural puncture headache, for which there is specific treatment. This happens on average about 1 in 200 spinal injections. This headache is usually worse if you sit up and is better if you lie flat. The headache may be accompanied by loss of hearing or muffling or distortion of hearing.

Rare complications of spinal anaesthesia

Nerve damage – this is a rare complication of spinal anaesthesia. Temporary loss of sensation, pins and needles and sometimes muscle weakness may last for a few days or even weeks, but most disappear with time and a full recovery is made.

Permanent nerve damage is rare (approximately 1 in 50,000 spinals). It has about the same chance of occurring as major complications of having a general anaesthetic.

Frequently asked questions of spinal anaesthesia

Can I eat and drink before my spinal?

You will be asked to follow the same rules as if you were going to have a general anaesthetic. This is because it is occasionally necessary to change from a spinal to a general anaesthetic. The hospital should give you clear instructions about when to stop eating and drinking before your surgery.

Do I have to stay fully conscious?

Before the operation, you and your anaesthetist can decide together whether you remain fully awake during the operation or would prefer to be sedated so that you are not so aware of the whole process. The amount of sedation can usually be adjusted so that you are aware, but no longer anxious. It is also possible to combine a spinal with a general anaesthetic but this does mean there are risks of both a spinal and a general anaesthetic.

Will I see what is happening to me?

A screen is placed across your body at chest level, so that you can’t see the surgery. Some operations use video cameras and telescopes for ‘keyhole’ surgery. Some hospitals give patients the option to see what is happening on the screen.

Do I have a choice of anaesthetic?

Yes usually, depending on the actual surgery and any potential problems with you having a spinal. Your anaesthetist will discuss choices with you.

There are uncommon reasons why you may not be able to have, or may be advised not to have, a spinal anaesthetic. These include having:

certain abnormalities of your spine or previous surgery on your back

‘blood thinning drugs’ that cannot be stopped or abnormalities of your blood clotting

infection in the skin of your back or a high temperature

certain heart conditions.

Can I refuse to have the spinal?

Yes. If, following discussion with your anaesthetist, you decide you do not want one or are still unhappy about having a spinal anaesthetic, you can always say no.

Will I feel anything during the operation?

You should not feel pain during the operation but for some procedures you may be aware of pressure as the surgical team carry out their work.

Should I tell the anaesthetist anything during the operation?

Yes, your anaesthetist will want to know about any sensations or other feelings you experience during the operation; this is part of their monitoring of the anaesthetic.

Is a spinal the same as an epidural?

No. Although they both involve an injection of local anaesthetic between the bones of the spine, the injections work in a slightly different way. With an epidural a fine plastic tube remains in your back during the operation meaning that more anaesthetic can be used as necessary.

Where can I learn more about having a spinal?

You can speak to your anaesthetist or contact the pre-assessment clinic or anaesthetic department in your local hospital.

Epidural

What is an epidural?

An epidural is a fine, flexible tube placed in the back near the nerves coming from the spinal cord, through which pain-killing drugs can be given to give pain relief.

It is used during surgery (usually in addition to a general anaesthetic), after the operation for pain control, or both.

Local anaesthetic, and sometimes other pain-relieving drugs, is put through the epidural catheter. This lies close to the nerves in your back. As a result, the nerve messages are blocked. This gives you pain relief, which varies in extent according to the amount and type of drug given. The local anaesthetic may cause some numbness and weakness as well as pain relief.

How is an epidural done?

Epidurals can be put in when you are fully awake or with sedation (drugs that make you sleepy and relaxed) .

Your anaesthetist will talk to you about which might be best for you.

-

The steps for having an epidural are:

- A cannula (drip) is placed in a vein in your arm for giving fluid

- You will be asked to sit up or lie on your side. You will be helped to bend forwards, curving your back as much as you can

- The anaesthetist will clean your back with antiseptic

- A small injection of local anaesthetic is given to numb the skin

- A needle is used to place a thin plastic catheter (tube) into the epidural space in your back. The needle is removed, leaving only the catheter in your back.

How will this feel (Epidural anesthesia)?

The local anaesthetic injection in the skin will sting briefly. There will then be the feeling of pushing, but usually no more than discomfort as the needle and catheter is inserted.

Occasionally, a sharp feeling, like an electric shock, is felt. If this happens, it will be obvious to your anaesthetist. They may ask you where you felt it.

A sensation of warmth and numbness gradually develops after the local anaesthetic is given. For some types of epidural, your legs may feel heavy and become difficult to move.

Overall, most people do not find these sensations to be unpleasant, just a bit strange. Feeling and movement will return to normal when the epidural is stopped.

What are the benefits of an epidural?

If your epidural is working well, after your surgery you will have better pain relief than with other methods, particularly when you take a deep breath, cough or move about in the bed.

You should need less alternative strong pain relief medicine. This means your breathing will be better, there should be less nausea and vomiting, and you are likely to be more alert.

There is some evidence that other complications of surgery may be reduced, including reduced risk of blood clots in the legs or lung and chest infection. There is also some evidence that you may lose less blood with an epidural, which would reduce your chance of needing a blood transfusion.

What if I don’t have an epidural?

It is your choice. Your anaesthetist will tell you if they particularly recommend an epidural, and what alternatives there may be.

Other pain relief methods use morphine or similar drugs. These are strong pain relief medicines but can have side effects that include nausea and constipation. Some people become confused when using morphine.

Alternatively, there may be other ways that local anaesthetic can be given – for example, a nerve block.

Can anyone have an epidural?

No. An epidural is not possible for some people. Your anaesthetist will discuss this with you if necessary.

-

An epidural may not be possible for you if:

- You take blood-thinning drugs, such as warfarin

- Your blood does not clot properly

- You are allergic to local anaesthetic

- You have significant deformity of the spine

- You have an infection in your back

- You have had previous surgery on the spine with metalwork in your back

- You have had problems with a spinal anaesthetic or epidural in the past.

Very common side effects of epidural anaesthesia

- Low blood pressure- It is normal for the blood pressure to fall a little when you have an epidural. Your anaesthetist will use fluids and drugs to correct it.

- Inability to pass urine- The nerves to the bladder are affected by the epidural. A catheter (tube) is inserted into the bladder to drain away the urine. This is often needed after major surgery with or without an epidural.

- Itching- This is a side effect of the pain relief drugs that are sometimes used in an epidural. Anti-histamine drugs may help, or the drug in the epidural can be changed.

- Feeling sick- This is less common with an epidural than with other pain relief methods. It may be helped by anti-sickness medicines.

- Inadequate pain relief- The epidural may not relieve all your pain. Your anaesthetist or the pain relief nurses looking after you will decide if it can be improved or if you need to switch to another pain relief method.

Common side effects of epidural anaesthesia

Headache

Headaches are quite common after surgery. It is possible to get a more severe, persistent headache after having an epidural. This happens on average about once in every hundred epidurals. It happens if the needle used to place the epidural or the epidural catheter unintentionally puncture the bag of fluid that bathes the spinal cord. A small amount of fluid leaks out, causing a headache. It can cause a severe headache that is worse if you sit up and is relieved by lying flat. The headache sometimes will go away on its own with good hydration and pain relief. The staff looking after you should alert the anaesthetic team as this will need to be reviewed by them before you are discharged. If the headache is severe or remains, you may need specific treatment for the headache. The headache may be accompanied by loss of hearing or muffling or distortion of hearing.

Uncommon side effects and complications of epidural anaesthesia

Slow breathing

Some drugs used in the epidural can cause slow breathing or drowsiness, which requires treatment.

Nerve damage: temporary

Uncommonly, the needle or epidural catheter can damage nerves. This can give loss of feeling or movement in a large or small area of the lower body. In most people this gets better after a few days, weeks or months.

Rare or very rare complications of epidural anaesthesia

Nerve damage: permanent

Permanent nerve damage by the needle or the catheter is rare:

permanent harm occurs in 1 in 23,500 to 50,500 spinal or epidural injections

paraplegia or death occurs in 1 in 54,500 to 1 in 141,500 spinal or epidural injections.

Catheter infection

An infection can occasionally develop around the epidural catheter. If this happens, it will be removed. It is rare for the infection to spread deeper than the skin. Antibiotics may be necessary or, rarely, emergency back surgery. Disabling nerve damage due to an epidural abscess is very rare.

Other complications of epidural anaesthesia

Convulsions (fits), severe breathing difficulty, permanent paraplegia (loss of use of one or more limbs) or death are very rare

- Why are you recommending an epidural for me?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of an epidural for me?

- What about the alternatives?

- Who will do my epidural?

- Do I have any special risks?

- How will I feel afterwards?

- How will I feel afterwards if I don’t have an epidural?

Regional nerve Blocks

About nerve blocks - eg. Brachial plexus block

The brachial plexus is the group of nerves that lies between your neck and your armpit. It contains all the nerves that supply movement and feeling to your arm – from your shoulder to your fingertips.

A brachial plexus block is an injection of local anaesthetic around your neck, collar bone or armpit to ‘block’ information (including pain signals) travelling along these nerves. After the injection, your arm becomes numb, heavy and immobile and you will feel no pain, although you may still feel movement and pushing or pulling as your arm is moved for you.

A brachial plexus block is designed to numb the shoulder and/or arm. It can be used instead of a general anaesthetic in some circumstances – this is particularly advantageous for patients who have medical conditions which put them at a higher risk from a general anaesthetic. Another advantage of having surgery under a block is that it may avoid some of the potential complications that may occur with general anaesthetics, like feeling sick or having a sore throat.

If you wish, you can be sedated when you have the brachial plexus block injections and/or during the operation. This may make you feel relaxed or drowsy but you will not be completely anaesthetised and you may be aware of your surroundings.

A brachial plexus block can also provide pain relief for up to 24 hours after surgery, although some areas may have reduced or altered sensation for up to 48 hours. It can be combined with a general anaesthetic. This means you have the advantage of the pain relief afterwards, but you are also unconscious during the operation.

Not only brachial plexus block, there are other blocks as well such as femoral nerve block, popliteal-sciatic nerve block etc according to region specific and operation specific are performed.

Your anaesthetist can explain the options available and what might be best for you. Please note that not all anaesthetists will be able to perform these specialist nerve blocks.

How the nerve block is performed (brachial plexus block)?

Having the injection you will usually be taken to a room near the operating theatre to have the nerve block.

The injection for a brachial plexus block can be either in the side of your neck, in your armpit, or close to your collar bone. Other nerves can be blocked near the elbow, or in the forearm, wrist or hand.

You may be offered sedation before the injection to help you relax and feel less anxious. If you are having a general anaesthetic as well, this may be given before or after the injection.

The skin around the injection site will be cleaned and a small injection of local anaesthetic will be used to numb your skin – it does sting a little as it goes into the tissues. The anaesthetist will use an ultrasound machine and/or a small machine that makes your arm twitch to locate the nerves.

Your arm will start to feel warm and tingly before finally feeling heavy and numb. The injection typically takes between 20 and 40 minutes to work. The anaesthetist will check the sensations you can feel at different parts of your arm and shoulder. You will not be taken to theatre until the anaesthetist is happy that the block is working well.

If the block does not work fully, you will be offered more local anaesthetic, additional pain relief or a general anaesthetic.

Side-effects, common events and risks of nerve blocks

Serious problems are uncommon with modern anaesthetics. Risk cannot be removed completely, but modern equipment, training and drugs have made anaesthesia a much safer procedure in recent years. Very common events after an anaesthetic include sore throat, sickness, thirst, shivering and bruising. Temporary memory loss may occur; this is more common in those who are over 60 years of age.

There are rare risks including damage to teeth and nerve damage. The risk of a severe allergic reaction to a drug is estimated at 1 in 10,000.

There is a very rare risk (1 in 20,000) of being conscious during a period of your anaesthetic. The risk of death directly as a result of an anaesthetic is estimated to be 1 in 100,000 for those people who are otherwise healthy.

Anaesthetists take a lot of care to reduce these events and risks. Your anaesthetist will be able to give you more information about any of these risks and the precautions taken to avoid them.

With increasing age and health concerns there are increased risks of blood clots in your legs or lungs and increasing risks of heart disease and stroke and even death around the time of an operation. You should discuss these risks with your surgeon, anaesthetist or pre-assessment team.

Questions you may like to ask your anaesthetist regarding nerve blocks

- Who will be doing the injection?

- What will I feel during the surgery?

- Do I have any particular risks from having this kind of anaesthetic?

- Do I have any increased risk from a general anaesthetic?

- What is the best option for me?

- What happens if the block does not work and I can feel pain? How often does this happen?

- When will my arm feel normal again?

- What number should I call if I am concerned about the after effects of the block?

Labour Analgesia

Labour Analgesia - Patient information for pain relief during labour Painless Delivery

Labour may be the most painful experience many women ever encounter. This patient information sheet will give you some idea about the pain in labour and what can be done to control it.

What will labour feel like?

Towards the end of pregnancy you may notice your abdomen tightening from time to time. When labour starts these tightening becomes regular and much stronger. This may cause pain that at first feels like strong period pain but usually gets more severe as labour progresses. Your first labour is usually the longest and hardest. Sometimes it is necessary to start labour artificially or to stimulate it if progress is slow, and this may make it more painful. Over 90% of women feel that they need some sort of pain control.

What will labour feel like?

- Relaxation is important and moving around sometimes helps. Having your back rubbed, can help you to relax and ease some pains away.

- Epidural is a technique where very dilute concentration of drug is used. Ask to see an anesthetist if you want further advice about pain control like patient controlled epidural analgesia or combined spinal epidural analgesia. Anesthetists are the doctors who provide epidurals. Epidural analgesia is the most effective method of pain control.

What to expect?

You will first receive a drip that is fluid running in the blood vessel of your forearm. The procedure will be performed by an anesthetist after wearing sterile gown, mask, gloves under sterile method in the operation theatre (OT).You will be asked to curl up on your side or sit bending forwards. Your back will be cleaned and a little injection of local anesthetic will be given into the skin, so that putting in the epidural needle will not cause pain. A needle will be introduced in your back short of spinal cord; a very thin bore plastic tube will be introduced and will be kept insitu for giving drugs to numb your pain. It is therefore important to keep still while the anesthetist is putting in the epidural, as care is needed to avoid puncturing the bag of fluid that surrounds the spinal cord. In combine spinal epidural technique along with epidural a small amount of drug is deposited in the bag of fluid surrounding the spinal cord. This relieves pain more quickly.

The pain-relieving drugs can be given as often as is necessary and/ or continuously by a pump. You can take extra drug yourself by hitting a button if you may need so. The machine has a safety feature where you cannot over drug yourself.

While the epidural is taking effect, your blood pressure will be noted regularly. The anesthetist will also check that the epidural is working properly. It usually takes about 20 minutes to work.

What are the effects?

- Pain control without numbness or heavy legs, in other words a ‘walking epidural’.

- Occasionally blood pressure falls, that is why you have the drip.

- Even with an epidural you are more likely to have a normal delivery

- It removes much of the stress of labor, which is good for the baby.

- Breast-feeding is not impaired; in fact it is often helped.

- Backache is common during pregnancy and often continues afterwards when you are looking after your baby. There is now good evidence that epidurals do not cause backache however may feel some local discomfort for a day or two afterwards.

- Other problems may happen in very rare cases.

- Epidural has no influence on the decision for caesarean section .Obstetrician will decide for caesarean section whenever it becomes necessary for the safety of the mother and the baby.

What if you need an operation?

If you should need any operation such as caesarean section or forceps delivery, you may not need a general anesthetic, as the epidural can often be used instead. A stronger local anesthetic and other pain-relieving drugs can be injected into your epidural tube to provide an adequate anesthetic for your operation. This is safe for you and the baby.

Have a happy and memorable labor analgesia and Motherhood

ICU – Patient Information

What is the intensive care unit?

The intensive care unit (ICU) is a special part of the hospital that provides care to patients with severe, life-threatening injuries or illnesses. ICUs have higher nurse-to-patient ratios than other parts of the hospital. They also can provide specialized treatments, such as life support.

It is a special area of the hospital where the focus is on intense observation and treatment with increased staff and resources. This helps respond immediately to emergency conditions. The trained nurses and doctors with the help of a multidisciplinary team ensure that the critical patient rapidly recovers and goes home to their family.

Who is an Intensivist / Critical Care specialist ?

Is a trained super specialist in the critical care medicine after completion of Anaesthesiology/ Medicine/Pulmonology and is responsible for the patients in the Intensive Care Unit. Major decisions are taken by Intensivist after discussion with the primary and referral consultants. Daily family meetings are done to brief the patient attendants about the health condition of the patient and the plan of care. The Intensivist holds a senior responsibility of the Unit and the other healthcare professionals work in coordination with him.

What is the difference between critical care and emergency medicine?

Critical care is the long-term treatment of patients who have an illness that threatens their life. Emergency medicine is the short-term treatment of those patients; it is also the treatment of patients who have a minor injury (for example, sprained ankle, broken arm).

In the emergency department, doctors and nurses stabilize patients and then transport them to the intensive care unit (ICU) or another area of the hospital for further treatment.

How does my primary care doctor fit into the care team?

Your family doctor is an important link between the care team and you.

The family doctor has a complete medical history of the patient, is often trusted by the family, and may be aware of the patient’s values, attitudes and healthcare preferences. The care team often works closely with the family doctor to determine pre-existing illness, allergies, use of medications, and other factors which may influence the health of the patient.

What kinds of illness require critical care?

-

Any illness that threatens life requires critical care. Poisoning, surgical problems, and premature birth are a few causes of critical illness. Critical illness includes:

- Myocardial infarction (heart attack)

- Shock

- Arrhythmia

- Congestive heart failure

Illness that affects the heart and all of the vessels that carry blood to the body, such as:

-

Illness that affects the lungs and the muscles used for breathing, such as:

- Respiratory failure

- Pneumonia

- Pulmonary embolus

-

Illness that affects the kidneys, such as:

- Kidney failure

-

Illness that affects the mouth, esophagus, stomach, intestines, and other parts of the body that carry food, such as:

- Bleeding

- Malnutrition

-

Illness that affects the brain and the spinal cord and nerves that connect the brain to the arms, legs, and other organs, such as:

- Stroke

- Encephalopathy

-

Infection caused by a virus, bacteria, or fungus, such as:

- Sepsis

- Ventilator-associated pneumonia

- Catheter-related infection

- Drug-resistant infection

-

Multiple organ failure

- A car crash

- A gunshot or stabbing wound

- A fall

- Burns

A serious injury also requires critical care, whether the result of:

What types of medical conditions are treated in the ICU?

There are many reasons that patients may be treated in the ICU. The most common ones are shock, respiratory failure and sepsis.

What is shock?

Shock is a condition in which vital organs are not getting enough oxygen because of low blood pressure. Shock can be caused by many medical conditions, such as heart attack, massive blood loss, severe trauma or sepsis.

What is respiratory failure?

Respiratory failure is lung failure that results in dangerously low levels of oxygen or dangerously high levels of carbon dioxide, which is a waste gas. Respiratory failure can result from lung conditions such as pneumonia, emphysema, or smoke inhalation. Respiratory failure can also be caused by conditions affecting the nerves and muscles that control breathing, such as drug and alcohol overdoses.

What is sepsis?

Sepsis is an infection that results in organ damage. When patients develop an infection, their bodies release chemicals to fight off the infection, but sometimes these chemicals can also damage vital organs, such as kidneys and lungs. When organs are damaged as a result of infection, this is known as sepsis. Any infection can lead to sepsis, but most commonly sepsis results from pneumonia, an abdominal infection (appendicitis or gall bladder infection), or a skin infection (for example, a cut that gets infected)

What sort of medical care happens in the ICU?

Patients in the ICU are very sick. They are often connected to many monitors that allow healthcare professionals to monitor their vital signs on a minute-to-minute basis. Patients often have intravenous tubes (IVs) in their arms and neck so that medications and fluids can be delivered directly into their veins. They often have a tube placed into the body to drain and collect urine. Some patients are also connected to life support machines, such as breathing machines or dialysis machines. Patients may also have a tube through their nose or mouth to deliver liquid food directly into the stomach. In order to tolerate the tubes, IVs, and life support, many patients receive sedating medications.

Why are there so many wires on the patient ?

The ICU is a place to monitor patients acutely. Fortunately modern technology has advanced a lot and we can get intricate details of a patient’s vital parameters like heart rate , breathing rate, oxygen level and blood pressure for example. This is done using multiple devices and these are the numerous wires that are seen which are constantly monitoring the patient.

Who needs to be treated in an ICU ?

Any patient who needs close monitoring and treatment needs to be admitted to an intensive care unit. Anyone with breathing difficulty requiring the use of special machines called ventilators , patients with low blood pressure needing medicine to treat it, infections causing septic shock as well as patients who need close observation after certain surgeries like heart bypass, trauma surgery and brain surgery are some examples.

What is life support?

Life support refers to various therapies that help keep patients alive when vital organs are failing.

Most often, when people say “life support,” they are referring to a mechanical ventilator, which is also known as a “breathing machine.” Mechanical ventilation helps patients breathe by pushing air into their lungs. The mechanical ventilator is connected to the patient by a tube that goes through the mouth and into the windpipe. Patients who need less lung support than mechanical ventilation may simply have a mask over their mouths and nose to deliver oxygen.

Dialysis is another form of life support; it filters toxins from the blood when kidneys are failing.

What is a Ventilator?

It is an artificial breathing machine helps the patient in breathing. It improves oxygen in the blood. It provides high concentration of oxygen and also has the internal settings in such a way that patient is more comfortable in breathing. Once the lung starts improving, the ventilator support will be decreased slowly and finally the support will be withdrawn. At every step the Intensivist will carefully analyse the situation and decrease the ventilator support.

What is a pressure sore?

The ulceration developed over the dependent parts of the body in the hospitalised patients, the pressure sore is more common in ICU patients due to immobility, same posture, severe infections, multiple comorbidities. Our pressure ulcer rate is very low due to continuous changing of position every 2nd hourly and early mobilisation.

What is ICU acquired infections?

HAI or Nosocomial infection or ICU acquired infections is the terminology used for hospital acquired infections. If a patient admitted to hospital/ICU more than 48hours with various reasons due to poor infection control measures the patient can get a new infection from other patient transmitted by the hospital staff (doctor or other staff). HAI or Nosocomial infection or ICU acquired infections burdens the patient by increase in mortality, morbidity and cost. We follow very strict infection control measures and are frequently audited.

How can I obtain copies of living wills and other documents?

Your local hospital and personal doctor are likely to have advance directives, living wills, and other documents available. A national organization, Choice in Dying, can also provide you with the forms.

Is it normal to have difficulty thinking after being hospitalized in an ICU?

Yes, patients often experience difficulty with everyday tasks such as shopping or balancing their checkbook. A recent study demonstrated that more than half of patients had difficulty thinking (also known as cognitive impairment) one year after having a critical illness. One-third of patients had cognitive impairment similar to that of someone who had had a traumatic brain injury, while one-third had cognitive impairment similar to that of someone with Alzheimer’s disease.

Is it normal to be nervous or anxious when remembering events that occurred while hospitalized in an ICU?

Posttraumatic stress disorder is a psychiatric condition that occurs as a reaction to a terrifying and traumatic event. It occurs in 10-20% of patients after critical illness. Patients might be anxious, have nightmares, avoid healthcare settings, and become disengaged.

Is it normal to feel depressed after hospitalization in an ICU?

Depression occurs in one out of three patients after critical illness. Symptoms of depression that might be experienced include prolonged sadness, loss of interest in activities that used to be enjoyable, inability to concentrate, changes in appetite, and changes in sleep.

Can I visit my family member or friend who is in the ICU ?

It is very important for family to be a part of the healing process . The presence of loved ones will reassure the patient . It is also very important that privacy is maintained , noise and infection are controlled and patients get time to rest and sleep. For these reasons visiting hours are specified outside the ICU .

The Visiting Hours are as follows: 11:00 am – 1:00 am .

Only 1 visitor is are allowed to meet the patient per day.